This is a summary and review of a book that Merna picked up during the SBL meetings in San Antonio, before Thanksgiving. She and I visited the Book Exhibit Hall and browsed books, something we were more free to do this year than in the past. The book that’s the subject of this post was spotted by Merna in the InterVarsity Press booth and she bought it, in part because we’d recently been in areas of the American southwest where First Nations people predominate and in part because of the mention of the Potawatomi, in whose lands we now live here in northern Indiana.

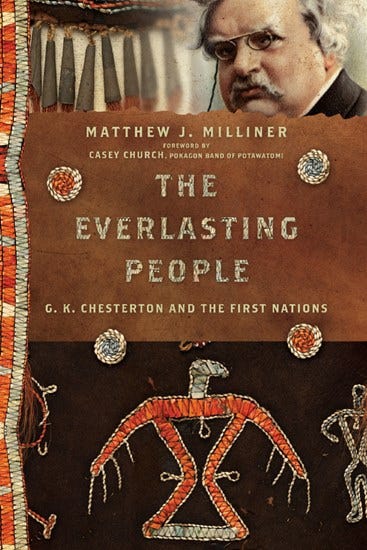

Full information: Matthew J. Milliner, The Everlasting People: G. K. Chesterton and the First Nations (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2021).

Milliner teaches Art History (primarily) at Wheaton College. I forget where I first ran into something written by him. He contributes to Comment and to his blog at millinerd.com. He’s also become interested in the history of America’s development at the cost of Indigenous Peoples, and this book is partly about that but quite a bit more. I’m grateful to be able to say that I learned much from this slim book.

“Turtle Island” is the name given by Anishinaabe to the land where they were born and grew up. This label is the term used by many of the Northeast and Midwestern Native Americans to the U.S. and, indeed, all of North America, as they knew it. They didn’t know about Europe, for instance, in the same way that ancient Israelites didn’t know about North America or South America, and so on. So the descriptions of the physical world that are found among the Anishinaabe are about North America, just as the descriptions of the physical world found in the Hebrew Scriptures are about the part of the globe we call the Near, or Middle, East.

The original peoples of the Midwest knew that Turtle Island had not always existed and they believed that the Great Spirit had been the primary actor in the creation of Turtle Island. And there was much more. (I’m hesitant to attempt to repeat it here, because I don’t think I can do it justice.) But what’s most important to note is that almost all European immigrants to the U.S. viewed Native American religion as primitive, superstitious, and deeply pagan—certainly not Christian.

What our history books do not record is that many Native Americans converted to Christianity and saw a significant alignment with their long-held beliefs about the nature of reality, about the creation of the world, and much more. And sadly, what frequently happened, even after those Native Americans came to Christianity, white Christians forced them off their lands, mistreated them, and sometimes killed them. Some of the violence toward Native Americans was a result of Protestant versus Catholic spite, which even the great Nez Perce chief Joseph recognized: “We do not want churches because they will teach us to quarrel with God, as the Catholics and Protestants do. . . . We do not want that.” [quoted from Milliner, p. 15]

What interests Milliner is to find ways in which Native American symbols and the beliefs to which they point can help us see ways in which God was active in native culture, including native religion. Appreciating Native American religious heritage, then, can also help us appreciate the horrors that immigrant Europeans visited on the earlier inhabitants of this land. This method, he says, is valid because “All that is good and true has proceeded from the Logos and has its homing-point in the incarnate God, even though this be hidden from us, even though human thought and human good-will may not have perceived it.” [pp. 17–18, quoting Hugo Rahner, Greek Myths and Christian Mystery, xiv]1

Milliner provides background to much of what he has to say with personal experience, because he has actively pursued more detailed knowledge of the history and culture of Native Americans. He weaves places he’s visited with events, some of which I’d heard of or noticed in some way but many of which I’d never known. An example:

In 1872, the Pennsylvania militia met [the Lenape converts to Moravian Christianity] at their settlement known as Gnadenhutten, “tents of grace” [in Tuscarawas County, Ohio].” American militiamen, falsely believing these Christian Indians had taken part in raids, voted to execute them. This was not the fever pitch of battle. The Americans thought it over. The Christian Lenape, mostly women, children, and elderly men, requested the night for prayer, which was granted. And in the morning, ninety-six of them “were beaten to death with mallets and hatchets, and scalped” as they sang Christian hymns. [Milliner, p. 27; citations from Chris Flook, Native Americans of East-Central Indiana, pp. 100–101]

How can one not weep?

This is just one story of many. Very little (if any!) of this is in our history books. Most public schools have a unit on state history that’s required of all students—this was true, at least, when I was growing up and our children had something like this. But none of this has been taught.

Milliner’s book recounts many more stories, but it’s hardly exhaustive in its recounting the tales of White peoples’ destruction of Native culture, religion, and the people themselves.

Part of what makes the book so interesting are two factors:

Milliner makes connections and parallels between ancient and medieval history, including the Christian wars of the Crusades, medieval Christian religious beliefs and iconography (he is, after all, an art historian), and the wars that America undertook against Native Americans from before the Revolutionary War through the 18th and 19th centuries. His dialogue with the writings of G. K. Chesterton are a significant part of the book, and Chesterton’s perspective on the Classical culture of Greece and Rome, seeing in them precursors to aspects of Christianity, is the road by which Milliner extends the spirituality of Native Americans to his understanding of Christianity.

What has happened in the last 200 years of American history is directly connected to where I live: northern Indiana, Potawatomi country, and quite near to major historical events including such notables I know a little about, including Chief Little Turtle (of the Miamis) and General “Mad” Anthony Wayne (I see you, Ft. Wayne).

How can I be unwilling to connect with the realities of the past, when they are geographically and intellectually—and spiritually—so close to home? We learn from history only when we face it, even if it was not the history of my personal actions or those of my ancestors (my mother’s family came from Prussia by way of Kansas, my father’s from Crimea). I live and move on land unjustly taken from others; the beauty I see from my window right now is that of “stolen land” (as the great Canadian songwriter, Bruce Cockburn, puts it so well).2

We cannot alter the past. We cannot undo the horrific, unjust things that the leaders of our country in the past inflicted on the native inhabitants of this land. In his Conclusion, Milliner introduces some suggestions for some directions that we can take. Here’s a personal story he tells that provides some food for thought. As part of a trip to Wheaton College’s Black Hills Science Station (in South Dakota) to teach a summer course in Native American art, Milliner and his family stopped at the Pine Ridge reservation:

[At] Oglala Lakota College, . . . we received a tour of the museum that told the Lakota side of the story of Paha Sapa [the Black Hills]. The fact that we would be comfortably sleeping that night in the Black Hills, while Oglala Lakota College resided so far away from their sacred land, was beginning to dawn on us. With some horror, I impatiently asked the Oglala Lakota College representative what we should do about that disjunction. At first she answered the question without words, offering an urgent look of restrained anger mixed with exhaustion. Then she spoke, “The sacred peak of what you call the Black Hills,” she told us, “is named after the Butcher of the Lakota, General Harney.” Though I did not know it then, she was referring to the killing of eighty-six Brulé Lakota, including women and children, at Ash Hollow in Nebraska in 1855. We had gazed on Harney Peak a few days earlier and read the vision Black Elk [Lakota chief] had upon it. We had learned how the “wounds in the palms of his hands” was aggressively editd out of Black Elk’s visions.3 The year after our visit, thanks to the efforts of Lakota Korean War veteran Basil Brave Heart, the name would be changed to Black Elk Peak. [Milliner, p. 131]4

Why would we resist the relatively small gesture of returning the naming of places to the original inhabitants of the lands that we conquered (in the case of the Black Hills, mainly in the name of the gold that was mined there)? It’s a small gesture to grant some respect, at the least, to those whose land was stolen. Can we do more? What can we imagine that might, even at this late date, be helpful?

This is an inadequate summary and review. If you’re interested in American (esp. Midwestern) history and the relationship between religions in general and Christianity, I highly recommend that you get a copy of The Everlasting People for yourself and read it, ponder it, and ask how you should be different.

This statement puts me in mind of Prof. Arthur Holmes’s (professor of philosophy at Wheaton College for many years) famous epigram, “All truth is God’s truth,” which has stuck with me through many years.

Bruce Cockburn, Stolen Land.

I’m a novice when it comes to understanding the “Ghost Dance,” which was a significant part of the Native American response to the U.S. Army’s conquest of the West, especially the northern tier of western states. Briefly, the Ghost Dance was a ceremony in which the Lakota and other tribes attempted a spiritual response to being conquered; for Christian Native Americans, it was deeply imbued with Christian symbolism, such that, for instance, Black Elk and others had visions of Christ. The massacre at Wounded Knee was a direct response to the Ghost Dance. I want to learn more.

I’ve not included citations to the sources that Milliner cites for the data provided in this chapter. They can be found on p. 131.

A small anecdote. On the trip Merna and I took through the American Southwest in October and November 2023, on our drive from Arizona to west Texas, we happened upon a site we didn’t know about: Hubble Trading Post, now a National Historic Site. Sometime, I may write that up at greater length, but today let me just report that we struck up a conversation with the Navajo (Dine) ranger in charge of the site. The exhibits moved me deeply; and I apologized for what my country had done to the Navajo. This led to a substantial conversation that, I suspect, the ranger doesn’t have with many visitors. The words he said that still haunt me were: “We Navajo will never catch up [to you Europeans who immigrated to North America].”

Thank you for this kind review!!